Data Quality in Virtual Clinical Trials

4 years ago

By Josh Neil

4 years ago

By Josh Neil

Arguably no other area in pharmaceutical science has suffered under Covid-19 like clinical trials have. The damage done by Covid-19 – to patient engagement, to supply chains and to hospitals – has shaken the industry.

But with such a crisis comes opportunity. There has never been a better time to look to the future. And in the clinical space, decentralised trials are the future.

Proventa’s new White Paper on the challenges and strategies of decentralised trials features facts and resources on the data, technology and regulatory aspects of virtual trials; an analysis of the challenges still facing the field; and expert judgment on potential solutions to these problems.

To mark the release of the White Paper, we’ve published a snippet from it below. The full version of the white paper is available at the bottom of the article. If you’d prefer to discover these insights firsthand, join online at our Clinical Operations, Supply Chain and Pharmacovigilance Strategy Meeting (25 June).

_____

The Issue of Data Quality in Decentralised Trials

Historically, collecting data via paper surveys and diaries is liable to inaccuracy and poor quality of data. This is not only from human errors, but from necessity of ensuring patient availability at certain times and places to complete PROs. Several studies on trials have found that patients often experience delays or fail to show up at all.

It has also been found that there are generally inconsistencies in how PROs are managed across different clinical trial centres. Clinical trial staff sometimes fail to respond correctly to these incomplete or overdue PROs, introducing biases to the data. Standardisation and better data quality are a must if the clinical trial model is to function at all.

The FDA has discussed the need for greater data quality in clinical trials, particularly around wearable tech. In the last few years it has published guidelines on electronic signatures and mobile technology.

Gareth Powell pointed out the ramifications of failing to improve data quality and safety. He said: “So far, the whole idea of patient data and how that’s handled hasn’t been done entirely well. There are still a lot of questions around the issue. Historically, patients didn’t feel that they were being informed where their data was going. When Google began accessing data at Moorfields Eye Hospital, for example, and using machine learning to predictively analyse de-personalised eyes for signs of eye disease, the hospital was criticised for handing data over to Google without a firm understanding of that data’s ownership.

“On the other side of that, we see patients keenly provide healthcare data to companies like 23andMe to directly support clinical research. So the desire to provide healthcare data is there, as long as individuals have control over that data and understand what it’s being used for.”

Maria Palombini argued that decentralising trials improved a patient’s right to privacy, and ability to consent more clearly on what they want to share in exchange for some transactional benefit. The current state of patient health data brings many complexities including the trial process. She raised the common issue of standardisation, with no taxonomies set up for health data: “current health data sits in a data swamp, not a data lake.” It would be very difficult and perhaps not very beneficial (from time or financial perspective) to try and clean up the “historical data baggage.” It would be more beneficial to adopt approaches and technical and data standards utilising technologies such as machine learning and open application program interfaces (APIs) to make health data portable with trusted applications and validated endpoints.

She stressed it is important for all of the industry’s stakeholders to engage and have a ‘voice’ in the development of technical standards. In highly complex regulatory environments such as pharma, regulators need to be included in the process in the development of the standard not only to contribute their expertise but to understand the nuances of how it can deliver a trust and viable approach to the problem.

Regarding the safety of patients’ data, many of the same problems remain as are found in regular trials, compounded further by greater quantities of data being taken and stored, and greater automation leading to a weakening of data ownership. Powell noted that, with the entrance of GDPR, clinicians are extremely wary of how they use patient data, especially when using more and more vendors to manage that process. Problems still remain, however, on how that information can be decentralised and stored safely.

Blockchain

One recent innovation pharmaceutical companies are looking to integrate into their trial processes is the private blockchain model. Unlike the more well-known public model, used by cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, the private model is more controlled and permission-oriented.

Due to the control relevant parties have over information, blockchain could prove particularly useful during the earlier stages of a trial, for example in monitoring consent. One study has set out the ideal open consent form using blockchain.

Maria Palombini noted that blockchain/distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) offer a significantly reduced risk to hacking depending how the application is deployed (public versus private) and consensus algorithms utilised (proof of work (PoW) vs proof of stake (PoS). “Right now, someone can hack a healthcare system and find a treasure of detail on 100,000 patient records or more. With an appropriately deployed decentralised DLT approach, if one patient’s device is hacked, then only that one patient would have been hacked!”

Beyond safety, blockchain has promise with regard to trial data and feedback. Currently, certain therapeutic states simply cannot be mobile or virtual, as patients will always need to go on-site to be treated. Also, Internet of Things devices and autonomous data collectors on-site may not get tied back to the patient’s home data profile.

With blockchain however, one record of truth can be established that is fundamental to the patient and to the trial. Unlike current informed consent processes, where multiple copies exist on multiple platforms and changes made to one may not necessarily be carried over to others, leading to confusion, blockchain technology provides a constant, immutable source of true data.

Blockchain, quite simply, improves trial data integrity via secure, autonomous data collection. Clinicians do not have to worry about hacking or tampering. The potential for fraud is eliminated.

One difficulty still remains, however. The private model of blockchain means that patients who want to remove their data will find it difficult to access the right permissions.

_____

The issue of data quality is just one facet of conducting decentralised trials. Others, such as regulatory guidance and patient engagement, are further explored in the White Paper. You can find more information on these and other key concepts in the full Clinical Development White Paper, available to download here.

Joshua Neil, Editor

Proventa International

To ensure you remain up-to-date on the latest in clinical development, sign up for Proventa International’s online Clinical Operations, Supply Chain & Pharmacovigilance Strategy Meeting 2020.

How to Reduce the Cost of Clinical Trial Supply Chain While Maintaining Quality and Efficiency

Clinical trial supply chain is a critical component of drug development, ensuring that drugs are available for testing, regulatory approval, and distribution. However, managing this supply chain can be challenging, with factors such as cost, quality, and efficiency all coming...

1 year agoHow to Reduce the Cost of Clinical Trial Supply Chain While Maintaining Quality and Efficiency

Clinical trial supply chain is a critical component of drug development, ensuring that drugs are available for testing, regulatory approval, and distribution. However, managing this supply chain can be challenging, with factors such as cost, quality, and efficiency all coming...

1 year ago

Raising Representation in Clinical Trials: An Interview with Liz Beatty, Inato

The COVID-19 pandemic created a significant shortage of suitable patients for clinical trials worldwide. Within this crisis was another more serious issue around inclusion and representation, driven by COVID’s disparate effect on certain ethnicities, that spoke to a wider issue...

3 years agoRaising Representation in Clinical Trials: An Interview with Liz Beatty, Inato

The COVID-19 pandemic created a significant shortage of suitable patients for clinical trials worldwide. Within this crisis was another more serious issue around inclusion and representation, driven by COVID’s disparate effect on certain ethnicities, that spoke to a wider issue...

3 years ago

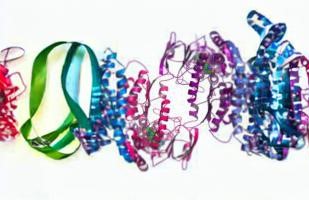

DeepMind’s AI Predicts Structures for More Than 350,000 Proteins

In 2003, researchers sequenced approximately 92% of the human genome, a huge achievement and very recently researchers have completed the entire process. Now, the latest innovation in AI technology has predicted the structure of nearly the entire human proteome. The...

3 years agoDeepMind’s AI Predicts Structures for More Than 350,000 Proteins

In 2003, researchers sequenced approximately 92% of the human genome, a huge achievement and very recently researchers have completed the entire process. Now, the latest innovation in AI technology has predicted the structure of nearly the entire human proteome. The...

3 years ago